With all of the advances in photography today, I started wondering about what the first camera ever created was like. I decided to do a bit of research to find out how it more.

So, who invented the world’s the first camera? Johann Zahn designed the world’s first camera and its capabilities, while Nićephore Níepce is credited with creating the first successful photo image.

Stretching back centuries, great minds had theories and hypotheses to the evolution of image capturing. Yet, it was Níepce who launched us into the future of permanent photography, giving us the oldest surviving photograph in history.

Contents

The Beginning of Photography

It all began with camera obscura. Camera obscura is derived from Latin, meaning “darkened room”.

Before photography could become a technique, we needed to understand optics and how we perceive images when manipulated by light.

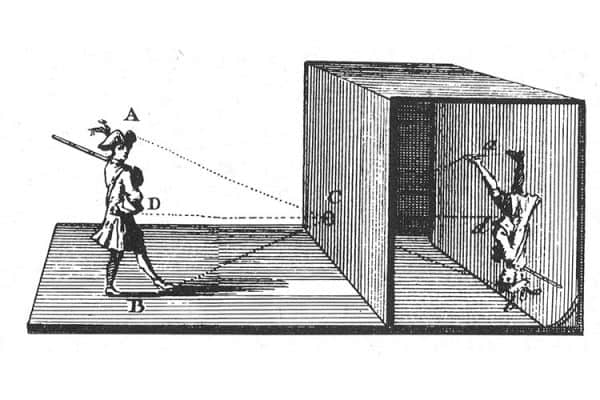

Way back when, it was discovered that when an image on the opposite side of a screen is cast through a pinhole, the image gets completely flipped around.

Technically speaking, the image becomes inverted. It is completely reversed and upside down.

So, why “camera obscura”? Well, in order to see the image clearly, there has to be little to no light surrounding the casted image. Hence, “dark room”.

Camera obscura, however, didn’t just refer to the act of casting light through a pinhole. It became the name of the actual device. Bingo! “Camera”!

This device was large and could even fill an entire room or be the room itself, using the camera obscura technique to cast an image.

The camera obscura device, however, was not a camera. It was not able to capture or record the image in any way. It was simply a projected image.

Often times, it was used for tracing art. I’m sure you’ve wondered how some artists were able to perfectly paint or draw an image of a person. The features and lines would be flawless and perfectly proportioned.

Several of these artists may have truly been that talented. However, I do not believe it is a stretch to assume that many of them used camera obscura to trace their subjects onto their mediums and add color later.

Camera obscura had many uses, and odds are, you’ve utilized it at least once in your life.

Do you remember those pinhole cameras you made in elementary school in order to safely watch an eclipse?

Camera obscura!

Think about it. The goal is to position your “camera” just right, so that the light from the sun will penetrate the hole, casting a shadow or image of the eclipse onto a wall.

This is exactly what was done in the early days of imaging.

Now let’s jump to the 17th century, shall we? Johann Zahn was the grandaddy of photography. Camera obscura made leaps and bounds in its development due to the creative (and possibly psychic) writings and illustrations of Johann Zahn.

He blew minds in 1685 when he published “Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium”.

This book was a collection of sketches and blueprints of many different optic viewing tools. From the camera obscura to telescopes and microscopes and even lenses themselves, Zahn’s blueprints opened up a whole new world of possibilities.

His illustrations were incredibly detailed as they depicted hundreds of theories and hypotheses on optics, lighting, imaging, and photography. Most of which would be proven correct long after his demise.

Yet, there is one theory in particular that opened the door to the beautiful and glorious camera as we know it today.

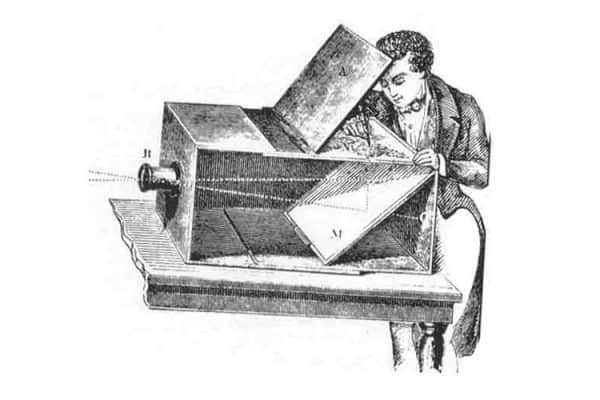

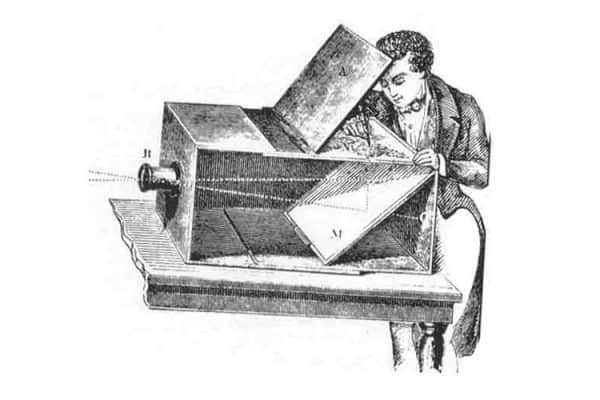

It was his visualization of a mobile, handheld camera obscura. That, of which, sent Níepce on his way into our history books.

Zahn envisioned a simple structure using a reflective mirror positioned at a 45-degree angle to cast the image. He also added a flap on each side to block unwanted light.

While this design was a thing of beauty, it would take nearly 150 years before Zahn’s sketches were brought to life.

Fast forward to 1816 and Nićephore Níepce throws his hat into the ring and develops the world’s first lasting image.

Nićephore Níepce was a French inventor and an expert in photography and optics. In 1816, Níepce wrote several letters to his sister-in-law explaining how he was able to capture live images. Thus, the first photo image was born!

He explained how he used a rudimentary version of Johann Zahn’s design of camera obscura and silver chloride coated paper to capture his image. However, the image developed as a negative where the light and dark spots were inverted.

Níepce needed another plan. He called it “heliography”. In around 1822, Níepce created the process by taking bitumen of Judea, a natural form of asphalt and coating a plate of metal or glass. Parts of the plate that was exposed to light, harden the coating. He would then wash the play with lavender oil, leaving only the hardened portions behind.

This process was used to create the very first permanently captured image. Níepce, however, destroyed the print when he tried to make copies from it. His first surviving photo, a view from his upstairs window in his home in France, llies safely at the University of Texas-Austin.

One Step Closer to the Camera

The process of heliography was unprecedented and changed the camera game forever. However, there was one issue; time. Heliography, meaning of “sun drawing”, required a photo plate to be exposed by the sun for multiple hours or even days.

Níepce was not known for his patience. So in 1829, he partnered with Louis Daguerre, a stage decorator and theater designer.

Daguerre was a curious student of lighting and optics, of which he craftly used in his work. He became a skilled panorama painter and received praise and recognition for his invention of the diorama.

Theatre would have to wait, however, as Daguerre and Níepce teamed up. They began experimenting to find a better alternative to heliography.

In 1832, they came close with a process called “physautotype”. They used lavender oil residue as a solvent when coating a polished plate. They continued with the heliography process and it worked. The image was successfully captured but the solvent wasn’t potent enough, causing the image to completely fade over time.

Níepce and Daguerre continued to experiment rather unsuccessfully. Then, in 1833 Nićephore Níepce died suddenly, ultimately ending the partnership.

Níepce’s Legacy

After Níepce’s death, Daguerre continued to experiment with different techniques. Soon after, he struck gold. He found a process that significantly decreased exposure time and could create a lasting image. He named it “daguerreotype”.

In the process, a sheet of silver-plated copper was polished to create a mirror. The plate was then treated with iodine vapor, making light sensitive to the plate.

It was then exposed to mercury vapor allowing the image to become visible and then fixed with sodium chloride to remove its light sensitivity. Once the image was successfully captured, it was placed behind glass to be preserved.

Daguerre decided to take his work publicly. In 1939, the French government bought ownership of the process. Níepce’s nephew, however, was none too pleased with Daguerre’s sudden fame and hefty payday.

He felt that Daguerre took credit for his uncle’s work. In the end, the French government agreed to pay both Daguerre and the Níepce estate.

Even with the payout, Níepce received little recognition for his work and advancements, while Daguerre absorbed the spotlight. It wasn’t until the 20th century that Níepce got the recognition he deserved.

Credit for the First Camera goes to…

Camera obscura, heliography, daguerreotype.

None of these techniques would have been created if not for the early pioneers in optics and the study of light.

Mozi, a Hans Chinese philosopher, is credited with having the oldest mention of camera obscura and his reason for the inverted projection. Mozi theorized that because light moves in a straight line, the image cast will be upside down and reversed.

Ibn al-Haytham was an Arab philosopher who published “The Book of Optics”. In the book, he conducted detail experiments to prove optic theories. One experiment, in particular, was conducted to prove that light does indeed travel straight.

The set up for the experiment was similar to how the camera obscura works; a dark room with light passing through a small hole, creating an inverted image.

These proven theories led to the creation of a room-sized device capturing inverted images (camera obscura) and eventually to the handheld device designed by Johann Zahn and realized by Nićephore Níepce.

Related Questions

What did Níepce’s rudimentary camera look like? Níepce’s camera was similar to the camera obscura. A simple wooden light-proof box with a tiny pinhole on the back and a metal plate fixed inside to capture the image.

How was the photo of the world’s first camera taken? The image that has surfaced on the internet of “World’s First Camera” is a fake. The image actually depicts the world’s largest camera. There is no photograph of Níepce’s camera, only sketches made from descriptions.

Who created the world’s first digital camera? The world’s first digital camera was invented by Steve Sassoon in 1975, in which the image was captured onto a cassette tape in black and white.